Club harnesses new mind-controlled tech

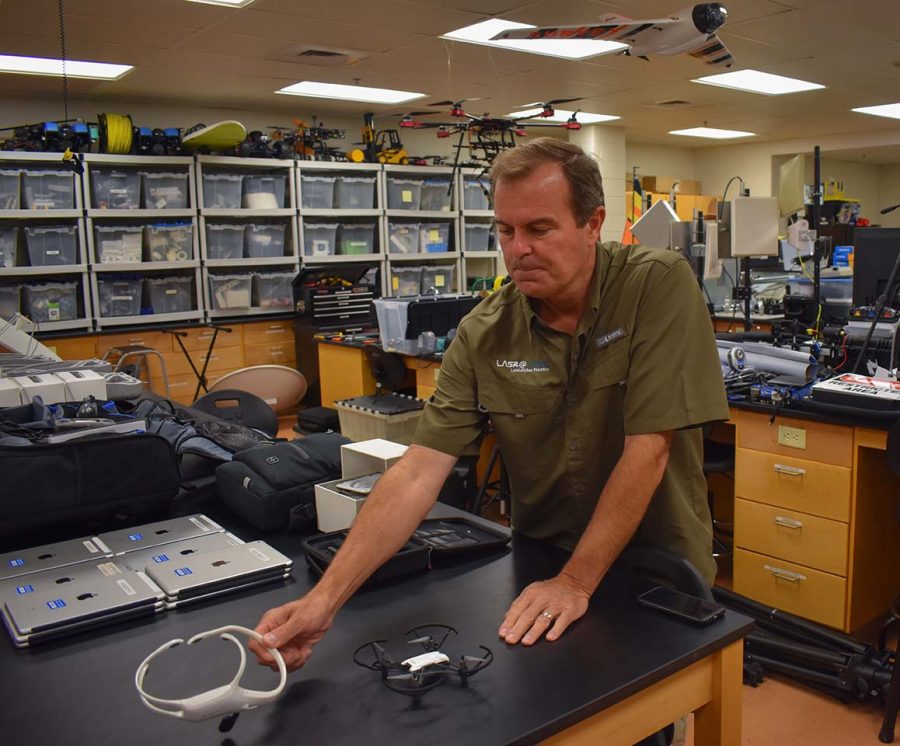

Drone Club members say they believe hands-free drone technology may allow disabled operators to perform more tasks. Pictured: Jim Blanchard, LASR program director.

October 1, 2019

Members of AACC’s Drone Club have programmed drones that they can operate using their brainwaves.

Former student Ciaran Dorland programmed the drones, while fourth-year entrepreneurial student Nick Kiraly and third-year transfer studies student Nathaniel Disney assisted with research.

“I think it’s amazing,” Disney said. “I think it has huge potential for many fields. We’ve only scratched the surface.”

Computer scientists around the world have been experimenting with mind-controlled drones for several years. The first mind-controlled drone race took place in 2016 at the University of Florida.

AACC’s Drone Club won the IEEE Brain to Computer Interface Competition in March 2019.

Hyper-focused drone operators wear headsets that read their brainwaves and translate their thoughts into commands for the drone to follow.

“We tell the drone when it sees [a specific] pattern to climb, or when it sees a different pattern, to descend,” said Jim Blanchard, who oversees AACC’s $2 million LASR Lab, which houses more than 30 drones.

“[The software] … has to know what you want the drone to do based on that [brainwave] pattern,” Blanchard said.

“You think commands, and the drone reacts to those commands based on software that interprets your brainwaves and tells the drone what to do. Your brain puts out an electrical impulse so the electricity is making it to the scalp. The [five] sensors on this headset … know the position on your brain so if [there are pulses on the sensors] it knows what you’re trying to think.”

Blanchard added: “So when you get those pulses together you get a complex brainwave pattern, and then we read that pattern into a database.”

Disney said the technology eventually could result in more accurate prosthetics for amputees.

Kiraly said hands-free drones could some day allow disabled operators to control their wheelchairs and “express themselves in ways they wouldn’t normally be able to without having dexterity.”

The drone technology also could expand into more practical uses, Blanchard said. For example, he said, “We could tell it to set a microwave to three minutes.”