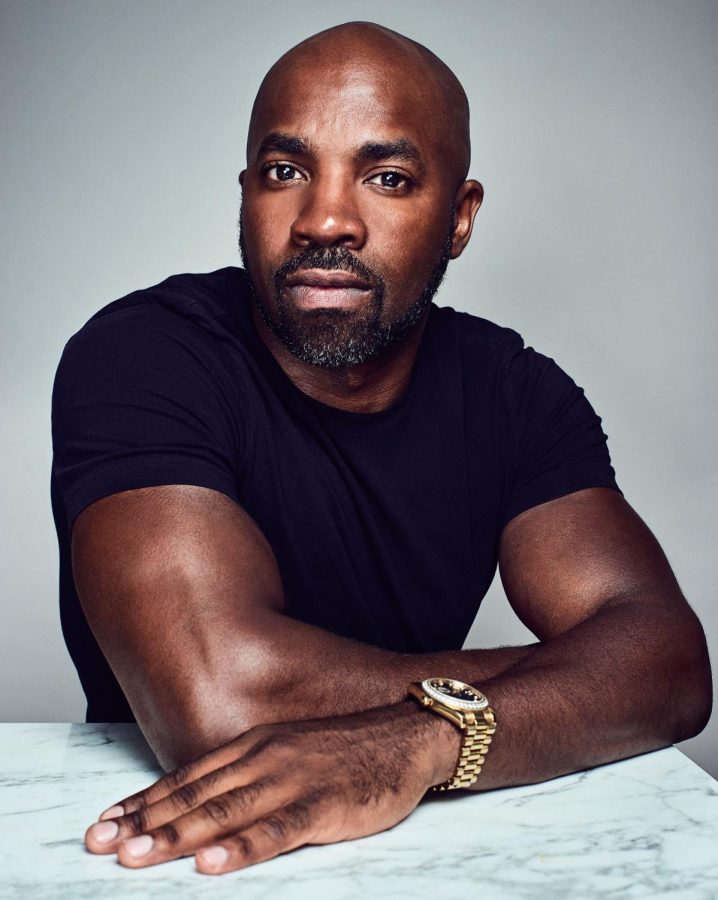

Ex-prisoner gets AACC degree, set to help produce film with Anonymous Content

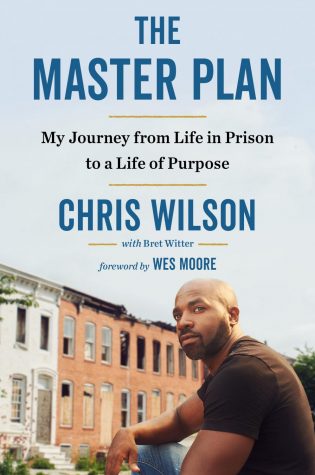

Former inmate at Patuxent Institution Chris Wilson got his AACC degree while serving time. He wrote a book called “The Master Plan: My Journey from Life in Prison to a Life of Purpose,” and plans to help Anonymous Content make it into a film.

May 1, 2019

This is the final installment in a three-part series on an AACC program to take community college classes to students in prison.

In June 1996, 17-year-old Chris Wilson walked outside of his home in Washington, D.C., where two men followed him down the block. In an attempt to escape them, he approached a 7-Eleven gas station, where customers were shopping and filling up their tanks.

The men cornered him.

“I had a gun on me, but I didn’t want to use it,” Wilson, author of “The Master Plan: My Journey from Life in Prison to a Life of Purpose,” recalled. “They came up to me and surrounded me. They said, ‘We’ve been watching you. We know where you live at. We know where your mom be at, and we’re going to take her out.’”

When one of the men tried to walk behind Wilson, he recalled, “I just pulled my gun out and started firing at him.” The other man darted one way, and Wilson ran another.

“And I found out I killed someone,” Wilson said.

For his crime, Wilson got life in a maximum security prison, Patuxent Institution in Jessup, in 1997.

But after 10 and a half years, judges reduced his sentence, to 24 years, and he served 16 and a half total.

He moved to a halfway house in 2011 and was free the following year.

As Wilson waited to make parole, he earned his associate degree in general studies from AACC, with a concentration in sociology. From 2001 until almost 2013, AACC sent professors to the prison to teach English, math, science, business and other courses.

Fifty-six prisoners graduated while the program was in progress.

“It changed a lot of lives,” Ed Duke, who remembers teaching Wilson, said. “Chris is an example that there are a lot of good in people who make mistakes, and there should be a chance for them to overcome those mistakes.”

Wilson said he took a wide range of classes while serving his time, including geography and sociology. He also founded The Foreign Language Club in the prison and started a book club with his fellow inmates.

“A big chunk of my incarceration was just studying and minding my business even though everything going on was crazy around me,” Wilson said. “My books and education allowed me to escape mentally.”

Wilson said the classroom setting at Patuxent differed greatly from that on the Arnold campus.

“There were people who would kill themselves, people who would overdose on drugs,” Wilson said. “There would be stabbings. When one person gets stabbed, even if it’s not in your house or unit, the whole institution would go on lockdown.”

He added: “It would be like, ‘Schools closed because someone got stabbed.’ Well I didn’t stab anybody. I should be able to go to school. You kind of got used to it, unfortunately.”

Duke, attending classes at Arnold from 1968 to 1973 and earning a Bachelor’s in math and a Master’s in computer science from Johns Hopkins University before he started teaching at Patuxent in 2002, said, “I had the freedom to go where I wanted to go. [The prisoners] had no way to get any outside information.”

Duke recalled saying, “It’s been a tough day, I’ve got to get out of here,” after one of his first classes at the prison. He said a prisoner from the back of the class yelled “Well, if you’ve been here for 20 years you’d think you really want to get out of here.”

Still, Duke and Wilson agreed that prisoners deserve to be educated.

AACC professors “were giving them an outside view of life and what the possibilities are,” Duke said. “People can change. They just need a chance and the right circumstances.”

Wilson graduated in 2006.

He described his graduation as “bittersweet.”

“None of my family showed up,” Wilson said. “Just my professors from the school, they showed up.”

Wilson said he is the only person in his family to earn a college degree besides his mother, who committed suicide in 2011 after he was released from Patuxent and living in a halfway house. His father was killed in front of his brother in November 1996.

However, Wilson said his dedication to learning brought him close to his professors and inspired him to make a difference in the lives of troubled youth once he got released in 2012.

He got his first job 52 days after release, as a community organizer and workforce developer for the nonprofit organization Greater Homewood Community Corp., now Strong City Baltimore. The organization works to restore Baltimore neighborhoods by offering academic, recreational and leadership opportunities for residents.

And he said his dedication to learning inspired him to make a difference in the lives of troubled youth.

“I’d rate him right in the top tier of people who wanted to learn and were self-taught when necessary,” said Steven Steele, a former sociology professor who taught at the Arnold campus and at Patuxent. “I hope people are inspired, not to feel sorry for Chris, but to see the method he used to become a new person.”

After his release, Wilson graduated from the Ratcliffe Entrepreneurial Fellows program at the University of Baltimore in 2015, where, he said, he realized that students in prison treat their educations differently from the way everyday students do.

“They are thinking about, ‘Oh, my social media page’ and, ‘Oh I have to go meet my friend later on’ or whatever,” Wilson said. “They don’t really know what they want to do and they have a safe place to go home and sleep.”

He said his classmates were often on their phones and not paying attention to the teacher.

“You’re paying for this. It’s an investment,” Wilson said. “In prison it’s like, ‘This is my rock bottom, and I have an opportunity to educate myself and accumulate some skills.’ … That’s everything.”

Wilson owns a construction company called Barclay Investment Corp. and a furniture design and manufacturing company called House of DaVinci.

Most recently, Wilson started a world tour for “The Master Plan,” which was published last winter.

“The book essentially is about my life story … growing up in a tough neighborhood,” Wilson said. “At my rock bottom, I decided I was a good person and my life was still redeemable, so I wrote up this master plan.”

Wilson described his master plan as a bucket list of everything he wants to learn, the places he wants to travel and the goals he wants to achieve.

“I wanted to go back to the toughest neighborhoods and create opportunities for people and be a positive example.”

He said he wants to inspire those behind bars, prisoners who have been released and anyone who isn’t happy with jobs or life.

“Anyone from any field of life could pick it up and learn something new and change their life,” Wilson said.

The production company Anonymous Content is turning Wilson’s book into a film.

“People [will] come away from this movie understanding that returning citizens are not all one and the same and there is work to be done in giving people another shot and rehabilitating them,” said Caron Williams, a creative executive at Anonymous Content who will work alongside Wilson to create the film.

“We want it to have a good reach. We don’t want to preach to the choir and only have people who already believe in prison reform [watching].”

Williams said she wants audiences to know that Wilson’s experience is not unique.

“Of course he is a special person, but I think what I got out of reading his book is that there are so many other Chris Wilsons, and that’s what makes the story so important,” Williams said. “He is an exception, but there are so many people in his situation that didn’t get support from the community around them.”

However, Duke said he has seen success with other prisoners like Wilson, pointing to one in particular who attended the University of Maryland after his release and earned his bachelor’s degree in sociology.

Duke said he remembers others starting their own businesses using the education they received in prison.

Although most professors at the prison said they lose track of inmates once they are released, Wilson said he keeps in touch with them, and most are doing well.

Between touring and producing his film, Wilson paints, sends his work to Paris and Italy, and sells it all around the world, he said. He is also a public speaker and philanthropist.

Just before publishing “The Master Plan,” he started the Chris Wilson Foundation in December, which funds academic scholarships at the University of Baltimore and offers financial support to prisoners who are trying to earn their bachelor’s degrees.

Wilson said he hopes his story will motivate students on the Arnold campus to take their educations more seriously.

“You may not take your classes seriously, and you may not know what you want to do with your life,” Wilson said. “Sit down and think about … what your end game is.”

Those who do that, he said, will “take your classes differently [and] push your school to provide that education for you, and if they’re not, demand it.”

Wilson said with the come-and-go culture of a community college, taking classes just to get a degree that will lead to a paid job is “a cop out.”

“There is so much more you can do with your life,” he said. “Take your life serious. There is no reset button.”

He said he would give the same advice to prisoners who take AACC classes.

“College is about demonstrating to others that you can accomplish difficult things, stick with something, work with other people and comprehend information,” Wilson said. “Sometimes you have to take classes and do work that you may not want to do in order to get to a place where you can do what you want to do.”

But he said not everyone supports prisoners getting an education.

“The country is set up. This is a business now,” Wilson said. “They don’t want you getting out [of prison]. How are they going to make money?”

Wilson said some people outside of the prison system reject the idea of inmate education as well.

“There are always going to people who are going to hate, like Twitter gangsters,” Wilson said. “They send me messages that say I should still be locked up.”

Wilson said education in prison betters society.

“I’m scared to death of someone who isn’t educated and then in prison all this time,” he said. “They could go out there and do anything and they do.”