Handlers say not to pet or touch service dogs

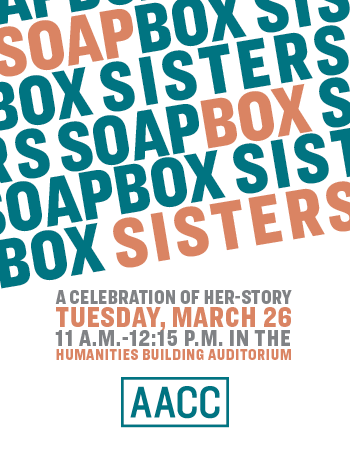

Photo courtsey of Catherine Wood

Four-year-old Sheltie Cody is first-year transfer studies student Catherine Wood’s service dog.

April 30, 2019

Service dogs are busy working and are not on campus for the public’s enjoyment, their handlers told Campus Current.

“Generally, people understand you’re not supposed to touch [service dogs],” first-year transfer studies student Catherine Wood said, “but you’re really not supposed to interact with them at all.”

Her dog, she said, is “a piece of medical equipment, equivalent … to a wheelchair or any other assistance thing.”

Wood has had her service dog, a 4-year-old Sheltie named Cody, since he was a puppy. Cody stays alert in case Wood feels lightheaded and anxious, and helps reduce and stop panic attacks quickly.

“It’s OK [for students who see a service dog] to be excited because it’s a dog, obviously,” Wood said. “And dogs make a lot of people happy, but you shouldn’t make a big scene. You shouldn’t call to the dog.”

She added: “Most people are out with their service dog to get something done in the day. They’re not out to stop and talk to people and this and that.”

Other service dog handlers on campus agreed.

“People are very intrusive,” veteran Michael Garvey, a journalism student at AACC, said. “They see a dog and they think you’re approachable, but I’m not. They start asking medical questions which is super annoying.”

Garvey added: “I always tell people, have you ever had the same conversation 40 times a day for five years? … Like: ‘Seven, black lab, 80 pounds, this, that,’ … over and over again. I just want to go about my day.”

Garvey, who has had his service dog, Liberty, for five years, said his dog helps him with mobility and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Trained dogs can serve as seeing-eye dogs, allergy alert dogs, seizure alert dogs, psychiatric service dogs and many other services.

Dr. Jessica Rabin, an AACC English professor, is training her third service dog, a four-month-old Airedale puppy named Caleb, to assist her with hearing. Her dog alerts her to the sounds of traffic, people nearby, phone calls and where she drops things.

“When I was between dogs it was kind of scary, living by myself,” Rabin said. “So that comfort of knowing that if there is a sound I need to know about, my dog is going to tell me about that. … It really is a tremendous difference in terms of independence, safety, security and awareness.”

Rabin said although service dogs are well trained and disciplined, they are still dogs and can have their moments.

“As well trained as they are, every dog can have an off day,” Rabin said, “and so we have to kind of remember that, forgive them for that and not have unrealistic expectations for them, both from a handler’s perspective and in the public.”

She added: “The law does not say that a service dog can never make a mistake. The law says that the handler needs to be able to get the dog back where it needs to be quickly and without making a disruption.”

Wood agreed with Rabin.

“When [Cody] goes home, he has plenty of time to be a dog,” she said. “He runs around the back yard with his brothers and makes noise. … He has time to be a dog and time to be a worker.”

Although AACC does not require owners to register their dogs, the federal Americans with Disabilities Act allows them to bring their animals wherever “the public is normally allowed to go.”

Wood said she has seen dogs on campus that clearly are not service animals. She said those dogs sometimes distract Cody, which can prevent him from doing his job and potentially put her in danger.

Some dogs are service animals and others are “comfort” or “therapy” dogs, whose training is different from service dogs.

On campus, students say service dogs as necessary and a part of life.